Good stories, for me, have never been treacly. My father, an RCMP officer, put people in jail; my mother, a halfway house director, put them back into society. My childhood was one of sensational publications and limited adult supervision. By age 11 I’d read Jaws, Helter Skelter and The Eden Express, a memoir of schizophrenia. I’d absorbed ghost stories, crime chillers and every “Drama in Real Life” article in every Reader’s Digest in the house.

Good stories, for me, have never been treacly. My father, an RCMP officer, put people in jail; my mother, a halfway house director, put them back into society. My childhood was one of sensational publications and limited adult supervision. By age 11 I’d read Jaws, Helter Skelter and The Eden Express, a memoir of schizophrenia. I’d absorbed ghost stories, crime chillers and every “Drama in Real Life” article in every Reader’s Digest in the house.

As an adult, I loved Stephen King. I bought books on wilderness deaths, eating disorders, sexual fetishes and Everest disasters. I investigated harassment complaints and edited reports on workplace fatalities.

So in 2016, when a friend mentioned a manuscript she didn’t have the stomach to edit, I figured hey, I can do it.

The subject? Bestiality.

I flinched when she said it. (So much for being tough.) But as my friend described the project, a mixture of true crime and sociology by a journalist who’d chased the story for years, I was intrigued. “Send me the lead,” I said.

The lead was, surprisingly, a pitch letter, complete with blurbs by other journalists who’d read the manuscript, seeking an editor willing to take on the topic. “I need to find someone who is comfortable editing words written about this subject,” wrote Carreen Maloney, the author, “or this will be an awkward and less-than-inspiring experience for both of us.”

I thought on it, I talked to Maloney, I talked to my husband. And I said yes. I worked on Uniquely Dangerous over the next year, doing two passes before the book was published in 2018.

Why?

Partly it was the author’s appeal. Maloney is a professional writer, a meticulous researcher and an animal advocate. She was passionate about her subject and had written a serious book.

Partly it was the challenge. As Maloney wrote, “Being able to confront these issues takes a certain kind of brain wiring, an intellectual curiosity about human spirit and behaviour that transcends revulsion.” Did she know I’m a sucker for a dare? I don’t think so, but it worked.

But the biggest draw was the chance to work on a topic that’s almost never written about. Why is zoophilia so taboo? Why does society say it’s fine to brand, castrate and confine animals but unnatural to love them as zoophiles do? How widespread is zoophilia? Is it a hard-wired sexual orientation? The questions that Uniquely Dangerous tackles have largely gone unposed because of the feelings they provoke.

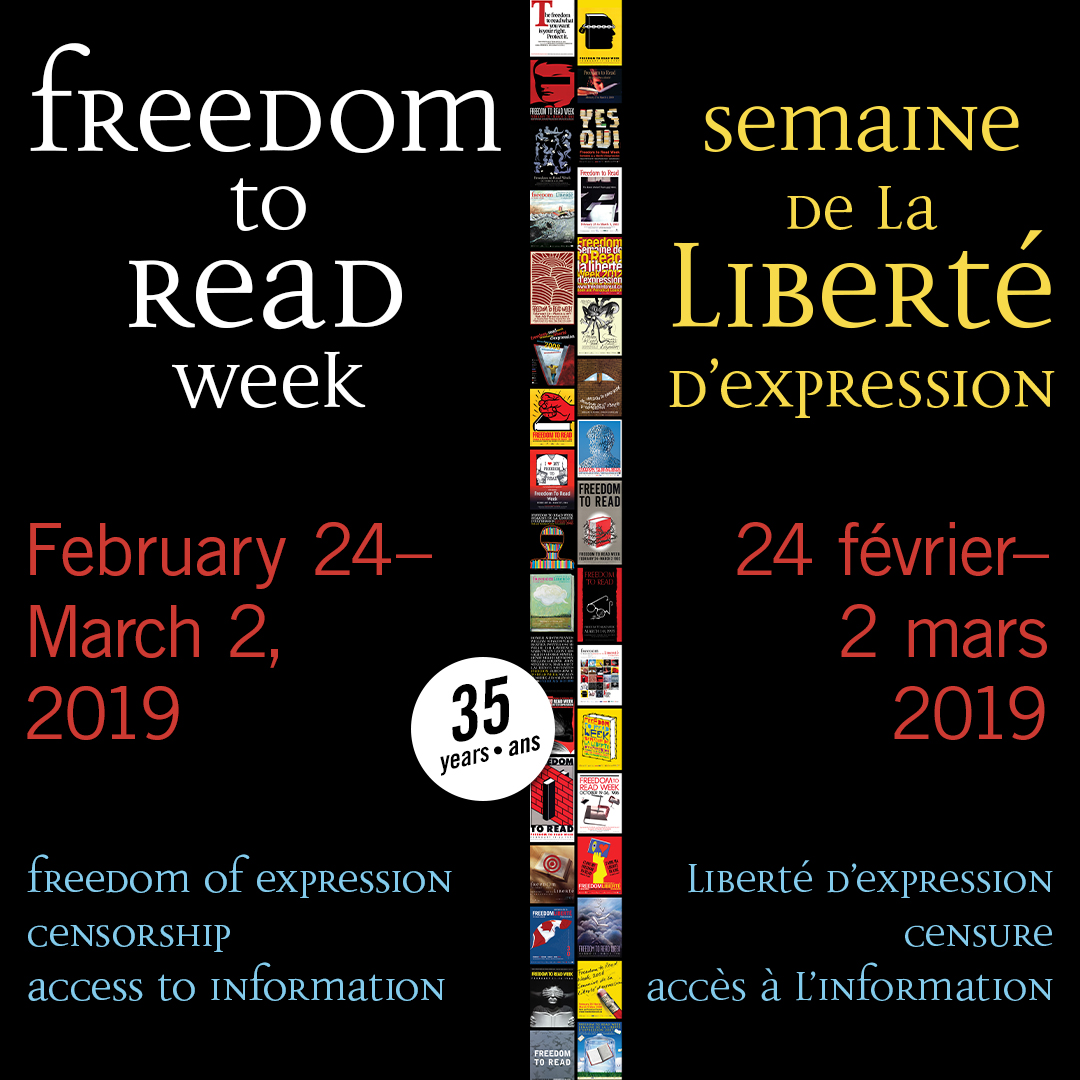

“Degrading, dehumanizing filth” — that was the reaction of one reader. Not to Uniquely Dangerous but to Margaret Laurence’s novel The Diviners. Surprised? Attempts to ban Laurence’s classic Canadian fiction in Ontario schools were what led the Book and Periodical Council to create Freedom to Read Week, which marks its 35th anniversary this week.

Freedom to read matters because filth, to quote songwriter Tom Lehrer, is in the mind of the beholder. Or as June Callwood said, in her 1993 Margaret Laurence lecture for the Writers’ Trust of Canada, “the speech with which you agree . . . is not threatened. The freedom of speech we must protect is the freedom of speech with which we explicitly, emphatically, categorically disagree.”

A free society must allow publications on controversial topics. We’ll never understand zoophilia if we don’t write about it, and writing about it means editing it.

Have you edited material on controversial or taboo subjects? Have you had to defend freedom to read?

___

Previous post from Frances Peck: A Little Strategy, a Lot of Satisfaction.

The Editors’ Weekly is the official blog of Editors Canada. Contact us.

Discover more from The Editors' Weekly

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.