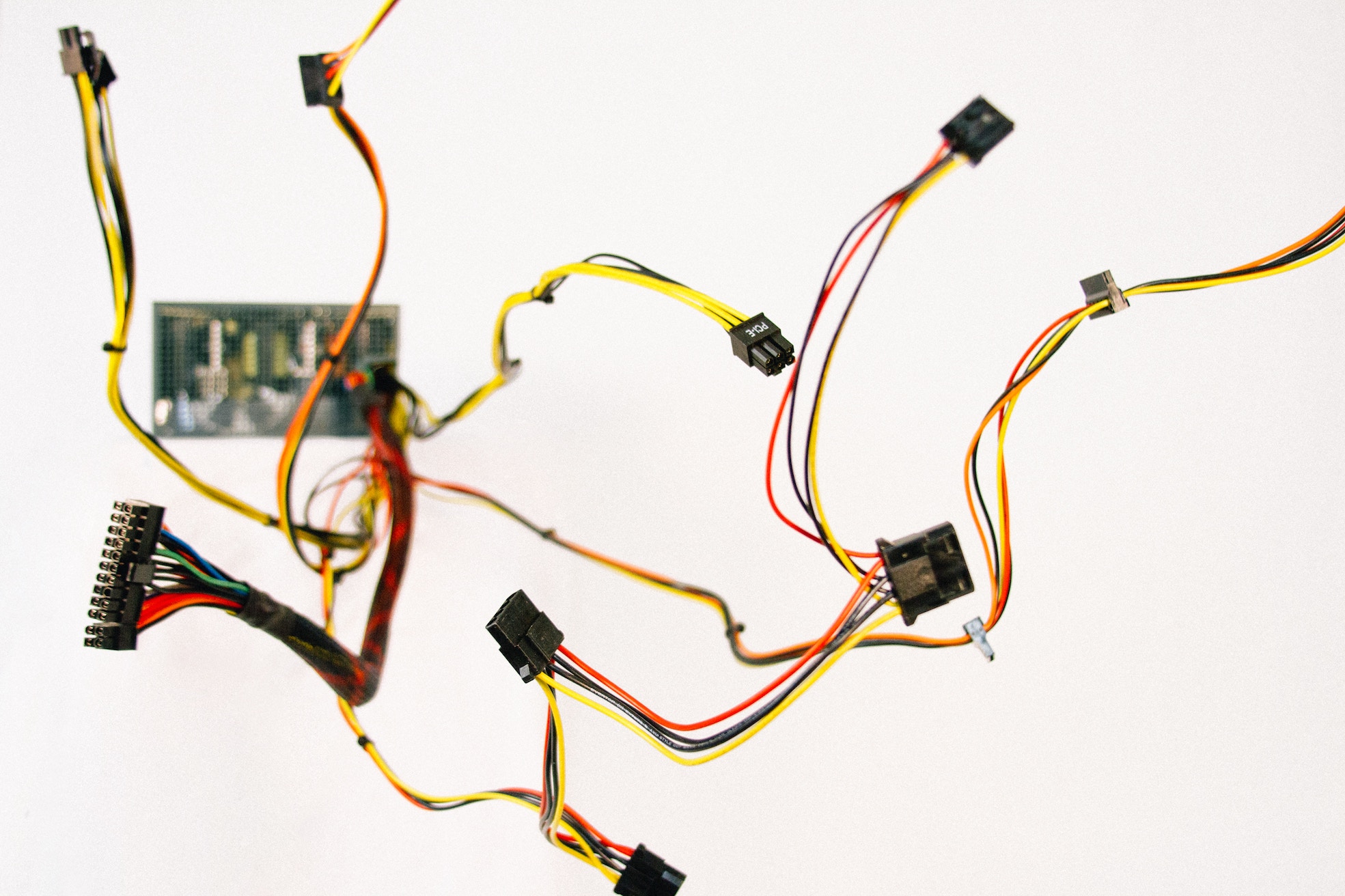

“How can you edit that? You don’t know anything about being an electrician.”

I often heard that question and variations of it — carpenter, instrument technician, welder — in my years editing technical instructional materials for apprenticeship trades in Alberta. This is how I answered the question.

I am the target audience

The goal of training materials is to teach the reader. The subject matter expert’s high level of expertise can cloud his or her ability to identify and stick to the basics that students who are new to the field need. It’s also easy for the expert to make the unconscious assumption that students have sufficient background experience to understand the concepts. Often that’s not true, which can lead to gaps in the information the expert provides. Those gaps may make it hard for students to grasp the concepts fully.

Some experts tend to write with others at the same level in mind, and they forget that students are the audience. This oversight may lead to unnecessarily complex writing and/or unexplained jargon.

As someone who knows nothing about being an electrician, I am the target audience for the training materials. If I can’t understand what the writer is saying, the odds are high that a student won’t either, so I edit the information through that lens. I can help the expert/writer fill in the gaps and simplify the language through how I frame my queries.

- I ask for definitions of terms.

- I rephrase unclear text and ask the writer to check if my meaning is accurate, or I ask the writer to rephrase when I understand too little of the text to reword it myself.

- I point out when a step in a process seems to be missing.

- I note materials that seem to contradict one another.

- I pose leading questions to show what information I think is required.

I am a language expert

I am not an expert in welding or carpentry, for example, but I am a language expert. Training materials are text like any other in many ways, so I use my expertise to address language issues that aren’t based in technical knowledge, such as grammar, sentence structure and content flow. I work in partnership with the writer, and we combine our expertise into a cohesive, comprehensive learning document.

These are my answers to “How can you edit that? You don’t know anything about being an electrician.” How do you answer similar questions?

___

For another perspective on whether you need subject expertise to edit, visit Sue Archer’s 2016 blog post, “Should You Only ‘Edit What You Know’?”

The Editors’ Weekly is the official blog of Editors Canada. Contact us.

Discover more from The Editors' Weekly

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.