As editors, we pay attention to the written form of our language. Its relation to the spoken form is a whole other thing.

The spelling is odd, we know. But even our hyphenation doesn’t really break according to pronunciation. Consider the word breaking. Where do you hyphenate it? Break-ing. But where does the syllable break happen in pronunciation? Before the k. Don’t believe me? Shout it, emphasizing each syllable equally. You’ll shout “Bray! King!” rather than “Break! Ing!” In speech, we automatically shift a consonant at the end of one syllable to the beginning of the next if there isn’t a consonant there already, regardless of how the word is formed. But in writing we reflect the bits the word is made of, because that’s how we think of it.

Except when we don’t. And then it’s a whole nother thing.

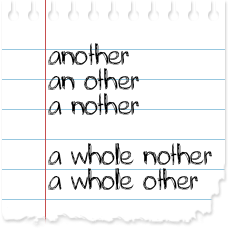

Take a word like another. It’s made of two pieces: an and other. Put them together, and the n is automatically said at the beginning of the second syllable, so it sounds like a nother. You’d think we’d still keep in mind that it’s really an other. You would not inevitably be right.

A whole nother isn’t the only place we’ve done this redivision. Centuries ago, a newt was an ewt and a nickname was an ekename. And speaking of nicknames, Ned and Nan come from mine Edward and mine Ann (we used to alternate my and mine as we still alternate a and an). And in Shakespeare you’ll see nuncle in place of uncle.

It also goes the other way. A poisonous snake, in English, was næddre, which would normally have become nadder, but instead of a nadder we have an adder. Likewise, a naperon gave us an apron. We pronounce them no differently, unless we put another word in between, but we think of them differently. We hear the n said at the start of the next syllable, but since the n in an always does that, we reanalyze it in a way that seems — for one reason or another — more appropriate.

Do you wish you could have someone to make rulings on these kinds of resplittings (also known as rebracketing and false splitting)? Try calling an umpire — as long as you don’t mind that your umpire would once have been a noumpere.

This doesn’t mean that we have to accept a whole nother, of course. A whole other is considered formally correct, although that implies a two-word an other. Since we’ve glued the two parts together, putting whole in the middle is arguably more like what we do in abso-bloody-lutely … except we wouldn’t write a-whole-nother.

Perhaps we should reconsider what we do and don’t think of as inviolable word boundaries. We may dislike alot quite a lot, for instance, but if we can make a word like another, can you think of a truly defensible reason for it not to be another such case? Or is that a … completely different issue?

~~~

Previous “Linguistics, Frankly” post: More Honoured in the Breach or the Observance?

The Editors’ Weekly is the official blog of Editors Canada. Contact us.

Discover more from The Editors' Weekly

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.